The growing ubiquity of wireless technology has sparked increasing awareness of electromagnetic hypersensitivity (EHS), a controversial condition where individuals report adverse health effects from exposure to electromagnetic fields (EMFs). While mainstream science remains divided on its legitimacy, the lived experiences of those who identify as EHS sufferers reveal a complex interplay between physiology, psychology, and environmental factors. These individuals describe symptoms ranging from headaches and dizziness to skin rashes and heart palpitations—all triggered by devices like Wi-Fi routers, cell phones, and power lines. What makes this phenomenon particularly intriguing is the stark variability in sensitivity thresholds between people.

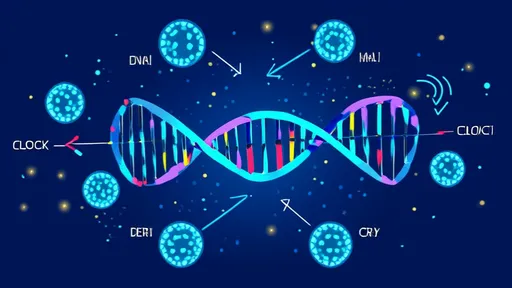

Research suggests that biological differences may play a role in how individuals react to EMFs. Some studies point to genetic polymorphisms affecting ion channel function or oxidative stress responses, potentially making certain people more susceptible to electromagnetic radiation. For instance, variations in the CACNA1C gene, which regulates calcium channels in neurons, have been linked to increased sensitivity to environmental stimuli. Meanwhile, other investigations highlight the role of the nocebo effect—where negative expectations induce real physical symptoms—complicating attempts to isolate purely physiological mechanisms. This duality underscores why EHS resists simple categorization as either a medical condition or psychosomatic disorder.

The diagnostic gray area surrounding EHS has profound implications for public health policy and urban design. Countries like Sweden and France officially recognize EHS as a functional impairment, granting sufferers accommodations such as shielded housing or wired internet alternatives. In contrast, regulatory agencies like the WHO maintain there’s no scientific basis for connecting non-ionizing EMFs to the reported symptoms. This disparity leaves affected individuals navigating a patchwork of medical skepticism and grassroots advocacy. Some clinicians now recommend multidisciplinary approaches combining environmental medicine, neurology, and psychotherapy to address both potential physiological triggers and the distress caused by chronic symptoms.

Emerging technologies are fueling new dimensions to the debate. The rollout of 5G networks, with their higher-frequency millimeter waves, has intensified concerns among EHS communities despite assurances about safety thresholds. Anecdotal reports of worsened symptoms near 5G infrastructure abound, though controlled studies remain scarce. Meanwhile, entrepreneurs have capitalized on the anxiety by marketing products like EMF-shielding clothing and pendant jewelry—often with dubious scientific backing. This commercial ecosystem further blurs the line between legitimate coping strategies and exploitation of vulnerable populations.

Beyond medical frameworks, electromagnetic sensitivity intersects with broader cultural narratives about technological progress. For some, it represents a cautionary tale of humanity’s unchecked embrace of wireless convenience; for others, it’s a case study in mass psychogenic illness amplified by digital misinformation. The condition’s elusive nature makes it a Rorschach test for societal attitudes toward science—is it a frontier of emerging environmental medicine or a rejection of established physics? What’s undeniable is that for those experiencing debilitating symptoms, the search for validation and relief remains deeply personal, often isolating, and far from resolved.

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025