For decades, the idea of selectively erasing traumatic memories has lingered at the intersection of science fiction and neuroscience. But recent breakthroughs suggest we may be closer than ever to turning this concept into reality. Researchers have identified a specific enzyme that appears to play a crucial role in memory formation and storage, opening up unprecedented possibilities for targeted memory modification.

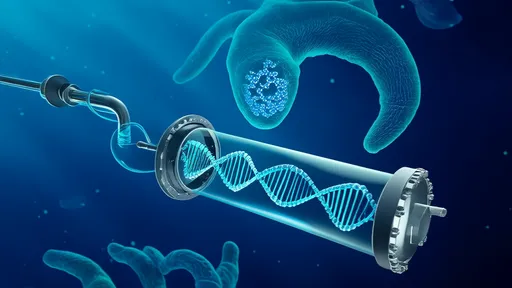

The discovery centers around an enzyme called protein kinase Mzeta (PKMzeta), which acts as a molecular scaffold for maintaining long-term memories. Scientists found that by inhibiting this enzyme in specific brain regions, they could effectively erase established memories in laboratory animals without damaging other cognitive functions. This finding challenges long-held assumptions about the permanence of memory and suggests our recollections may be more malleable than previously thought.

What makes this discovery particularly groundbreaking is its precision. Earlier attempts at memory modification often caused widespread neural disruption, but targeting PKMzeta appears to allow for selective memory erasure. The enzyme seems to serve as a sort of "memory glue," and when this glue is dissolved, specific memories disappear while leaving other mental faculties intact.

The research builds upon years of work exploring memory reconsolidation - the process by which recalled memories become temporarily unstable before being stored again. During this vulnerable window, memories can be altered or erased. PKMzeta appears to be a key player in this re-storage process, making it an ideal target for therapeutic intervention.

Traumatic memories differ from ordinary ones in their intensity and persistence. They create powerful neural pathways that can trigger debilitating flashbacks and anxiety responses. Current treatments like exposure therapy aim to weaken these associations, but often with limited success. The ability to directly target the biochemical basis of traumatic memory storage could revolutionize PTSD treatment.

Ethical considerations loom large in this field of research. The very idea of memory manipulation raises profound questions about identity and personal history. Would erasing traumatic memories fundamentally change who we are? Could this technology be misused to create artificial histories or remove inconvenient truths? The scientific community is grappling with these questions even as the research advances.

Practical applications remain several years away, but the potential is staggering. Beyond treating PTSD, this approach might help with phobias, addiction (where maladaptive memories play a key role), and even certain chronic pain conditions. The research also opens new avenues for understanding basic memory mechanisms, which could benefit conditions like Alzheimer's disease.

One surprising finding has been that memories erased through PKMzeta inhibition don't simply vanish - they appear to revert to a latent state. In some experiments, cues could temporarily revive "erased" memories, suggesting the information isn't entirely gone from the brain. This nuance could be crucial for therapeutic applications, allowing for more controlled memory modification.

The next challenge will be developing safe, targeted delivery methods for PKMzeta inhibitors in humans. The blood-brain barrier presents a significant obstacle, and any treatment would need to act on very specific memory circuits without affecting other brain functions. Early-stage clinical trials could begin within the next five to ten years if these hurdles can be overcome.

As research progresses, we may need to reconsider fundamental aspects of how we view memory. Rather than a fixed recording of the past, memory appears to be an active, dynamic process - one that we may soon learn to influence with unprecedented precision. The implications for mental health treatment could be transformative, but so too could the philosophical and societal consequences of this newfound power over our own minds.

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025